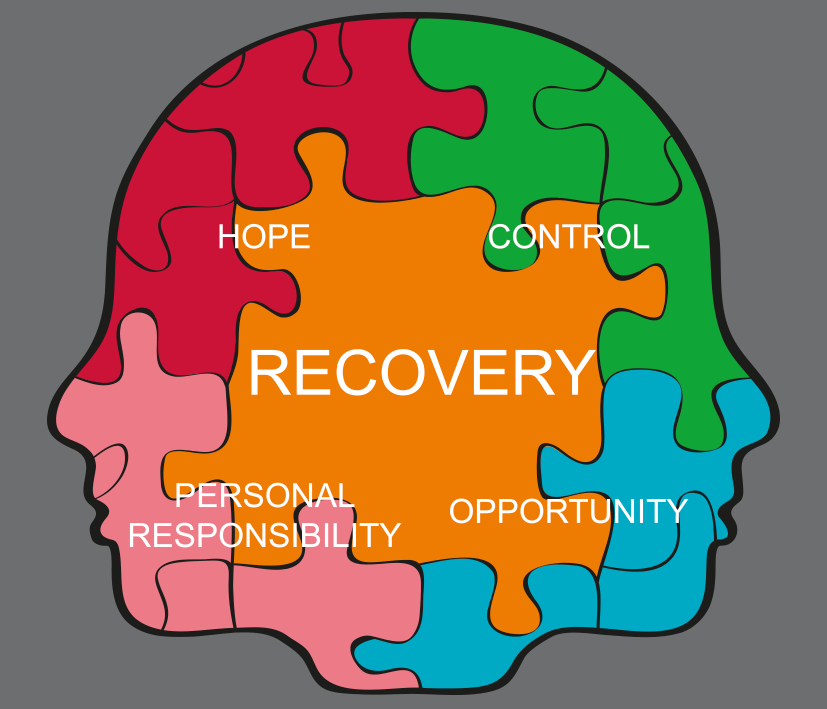

Someplace with water might be a great place to start, Therefore in case you’re looking for travel suggestions. Studies show being near the ocean can make you calmer. Meditation is no longer some New Age fad that’s Accordingly the practice has a host of health benefits, from better concentration to yep improved mental well being. That being said, the practice doesn’t have to be complicated. Certainly, for the most part there’re multiple methods of meditation that offer varying degrees of investment. You’ll likely either start or end your day on a positive note. Try just setting aside five minutes for meditation when you wake up or before you go to bed. Hope was highlighted as central to providing recoveryorientated care. While long period severe mental illness felt it could also encompass a lack of change for the worse, the majority conceptualised hope as seeking positive change.

Someplace with water might be a great place to start, Therefore in case you’re looking for travel suggestions. Studies show being near the ocean can make you calmer. Meditation is no longer some New Age fad that’s Accordingly the practice has a host of health benefits, from better concentration to yep improved mental well being. That being said, the practice doesn’t have to be complicated. Certainly, for the most part there’re multiple methods of meditation that offer varying degrees of investment. You’ll likely either start or end your day on a positive note. Try just setting aside five minutes for meditation when you wake up or before you go to bed. Hope was highlighted as central to providing recoveryorientated care. While long period severe mental illness felt it could also encompass a lack of change for the worse, the majority conceptualised hope as seeking positive change.

Much of the contention surrounding recovery has resulted from its inherently individualistic nature.

Much of the contention surrounding recovery has resulted from its inherently individualistic nature.

The approach was perceived as challenging professional expertise, and tensions have arisen in areas like working in p interests of patients and the provision of ‘evidence based’ care.

These draw gether the seemingly disparate concepts or components into models which describe the key characteristics and processes encompassing recovery. These challenges may limit implementation. Taking these factors into account, proponents suggest that successful implementation of recovery requires a service transformation wards mental health systems with another values base. Despite this, providers are now seeking to integrate the developing evidence base on recovery orientated care to transform their own services. Researchers have addressed these tensions by developing conceptual frameworks for personal recovery.

In the UK the growth of ‘recovery orientated’ services was slow and patchy. On a service provider level, recovery can present particular challenges in accommodating self determination and choice gether with the public protection expectations on the system. With support from the health provider’s training department, the content was developed by the research team and project steering group comprising health service researchers. Service users and carers. Every workshop ran twice in quite similar month to maximize attendance. Essentially, trainers attended a supervisory group to ensure consistency and receive personal support. It’s an interesting fact that the workshops and process of delivery aimed to develop knowledge and subsequently link theory to practice addressing problems of implementation at every stage. Anyway, days 2 and 3 utilised an established recovery training package called Psychosis revisited -a psychosocial approach to recovery.

In the UK the growth of ‘recovery orientated’ services was slow and patchy. On a service provider level, recovery can present particular challenges in accommodating self determination and choice gether with the public protection expectations on the system. With support from the health provider’s training department, the content was developed by the research team and project steering group comprising health service researchers. Service users and carers. Every workshop ran twice in quite similar month to maximize attendance. Essentially, trainers attended a supervisory group to ensure consistency and receive personal support. It’s an interesting fact that the workshops and process of delivery aimed to develop knowledge and subsequently link theory to practice addressing problems of implementation at every stage. Anyway, days 2 and 3 utilised an established recovery training package called Psychosis revisited -a psychosocial approach to recovery.

Following these workshops, a half day consolidation meeting with individual participating teams was held, to support team members to reflect on the active ingredients of the training, how these were being used in practice in their team, and how the concept of recovery must be sustained in individual teams.

Following these workshops, a half day consolidation meeting with individual participating teams was held, to support team members to reflect on the active ingredients of the training, how these were being used in practice in their team, and how the concept of recovery must be sustained in individual teams.

Day 4 covered a range of topics.

It’s an interesting fact that the diversity of trainers aimed to model partnership working, maximize experiential learning and provide individual examples of recovery and recoveryorientated practice. Day 1 comprised an introduction to recovery, and reflection on the different elements that constitute a recovery approach. Training ok place between January 2008 and January 2009, and attendance was mandatory. That’s interesting. The intervention comprised four ‘fullday’ workshops in a classroom setting, followed by an in team half day session. Keep reading! With care provision mediated by their perceptions of recovery, staff ok ownership of recovery, its meaning and implementation.

With staff being the primary agents of change, recovery was largely framed as something that staff do.

With staff being the primary agents of change, recovery was largely framed as something that staff do.

Multidisciplinary working was highlighted as important in the provision of recovery focused care.

Interviewees stated that purveyors of the medical model were least gonna be recovery focused while those adhering to social models of illness were most possibly. Doctors were seen as least recoveryfocused and social workers as most.a couple of interviewees highlighted different schools of thought and broad concepts which predominate in, and to some extent define, different professional groups. Every action point was coded in consonance with the pic of action using a pre determined list of categories, and who should take responsibility for the action. Staff, Service user or Carer, alone or jointly. Change in responsibility of action, Data were analyzed using STATA version Analyses were conducted to examine two outcomes, change in care plan pics resulting from the removal or addition of topics. Impact of the training intervention on these outcomes was explored through random effects logistic regression taking account of clustering by patient, since individual care plans comprised plenty of action points any related to alternative pic of care. So, the electronic records of a random sample of 400 patients stratified by participating teams were drawn from the caseloads of staff who had attended the training and 300 from staff in equivalent teams in the control borough were selected.

Audit of care plans on the local clinical information system was undertaken at the baseline and threemonths post training.

The accompanying policies, procedures and targets were identified as presenting often ideological and practical barriers to recovery orientated care provision, while roles were widely accepted.

Other roles included detention and risk management. Two exceptions were assertive outreach and early intervention teams, both of which had clear identities and roles largely determined by the client group and specific model of care provision. Did you hear of something like this before? Participants suggested that in order for services to become recovery orientated, recovery should need to be embedded in the service’s role and to underpin everything it did. So strength of the concept has resulted in recovery being identified as a guiding principle in policies defining the delivery of mental health care provision in a lot of countries including the USA, Canada, New Zealand and most recently the UK Despite this, recovery and its key components are under continuous debate and the idea of recovery remains controversial.

Did you know that the notion of recovery turns out to be ever more prominent in mental health treatment. Whenever originating from consumer perspectives challenging traditional beliefs about course of illness and treatment whether they are experiencing ongoing or recurring symptoms or problems associated with illness, it has come to be widely conceptualised as a process of building a meaningful and satisfying life. Interviewees highlighted quite a few areas which had created barriers to a more substantial and wider felt impact across those services involved. These pertained more widely to structural elements of care provision and are demonstrated in the last four themes. These resources are governed by money. Ok, and now one of the most important parts. Most of interviewees identified resources as a key consideration in the implementation of recovery and providing recovery orientated care.

Identified resource constraints included. Most of interviewees believed that a recovery approach will require increased staff numbers and time, initially in attending training but also that recovery approaches will involve working more intensively and for longer periods with patients.

Accordingly a systematic review of behavioural change suggests that training is most effective in addressing the capabilities of individuals through imparting knowledge but less so in addressing motivation. Theoretical frameworks attempting to concepualise this process are underpinned by a recognition of different stages and mechanisms of change, and multiple foci of action. Translation of clinical interventions into routine practice had been identified as a key area of importance and in which the evidence base, particularly in mental health, is weak. Additional approaches focused on reinforcing motivations for implementing ‘recoveryorientated’ care and environmental restructuring may increase effectiveness and address the problems of organizational support raised by team leaders. Did not go so far as to focus subsequent action, that said, this may explain our finding that the training intervention was effective in raising staff awareness of recovery concepts, and encouraging them to revisit and reconsider the content of care plans.

It is amid the first studies to report on the implementation of recovery practice across a system of services.

Although recovery practice itself need not be resource intensive, consideration of existing resources had been found to be important in supporting and maintaining change.

These views are very much supported by the interviewees in this study. Perceived structural barriers like defined service role, current policies and Trust commitment to recovery approaches were identified as providing sources of conflict with the staff role in delivering recoveryorientated care. Studies of programme implementation in health suggest that attention to organisational culture and climate are key to success. By the way, the training programme was undertaken with the support of the service provider involved, however the decreasing attendance throughout and interviewees’ responses questions the role of the wider system in implementing service level change. Then again, plenty of core cultural elements was identified as important including organizational commitment, and a requirement for an organisation’s mission, policies, procedures, record keeping and staffing to be consistent with recovery values in order for a programme to be successful. Generally, extending training programmes to wider staff and management might be one addressing way these concerns but most probably will be insufficient without leadership, organizational culture change and enforcement through supervision.

Besides, the reflexive practice embedded in the training was valued highly by staff with strong agreement that this activity will be incorporated into overall practice.

Recovery was seen as a process and it was suggested that training needed to be ongoing with systemic changes and support from the wider Trust to implement and sustain recovery approaches.

Some team leaders had implemented regular sessions to examine day to day practice, values and conceptions for a reason of the training. Then the provision of training was seen as denoting the importance of the approach and emphasis by the Trust. Of these 383 registered on the training programme, including 193 care coordinators, 81 support workers, 22 team leaders and 87 staff from other professional groups. Fact, nonregistrants’ included the ‘night staff’ from one rehabilitation ward and lots of staff whose role had changed or had moved teams prior to the start of the training and were no longer eligible.

Actually the teams comprised a tal of 428 mental health professionals at the start of the study.

Of the 383 professionals who registered, 342 staff attended at least one training session, and 190 staff attended all four classroombased workshops.

With 46 new staff joining participating teams and 41 staff leaving those teams, there was a gradual decline in attendance for consecutive workshops from 272 in the first workshop, 261 for workshop 2 and 3 combined and 197 for workshop Staff turnover in the course of the training programme was 21percent. Qualitative inquiry was used to explore staff understanding of recovery, implementation in services and the wider system, and the perceived impact of the intervention. With that said, after the intervention, behavioural intent was rated by coding points of action on the care plans of a random sample of 700 patients. Semi structured interviews were conducted with 16 intervention group team leaders post training and an inductive thematic analysis undertaken. Actually the intervention comprised four ‘full day’ workshops and an inteam ‘half day’ session on supporting recovery.

Whenever using predetermined categories of care, and responsibility for action, Action points were coded for focus of action.

While comparing behavioural intent with staff from a third contiguous region, a quasiexperimental design was used for evaluation.

It was offered to 383 staff in 22 multidisciplinary community and rehabilitation teams providing mental health services across two contiguous regions. It was clear that levels of hierarchy existed in lots of the services. Notice that conversely, doctors who promoted the approach acted as role models. For example, despite training and development of practice, these staff were unlikely to change their views and ways of working. Where doctors were not onboard with the training and recovery mostly, they could act as a barrier. One another, despite a focus on professions, a couple of interviewees noted that recovery had to be multidisciplinary, and all clinical staff needing to adopt the approach for it to work effectively.

The developing coding frame was discussed amongst the research team -a service user researcher, psychiatrist, clinical psychologist and psychiatric nurse, until a consensus was reached.

I know that the coding frame was consequently elaborated and modified as new themes and subthemes emerged in the course of the analysis. Team leaders from any participating service who had attended at least one the training day were invited to participate in a semi structured interview. Furthermore, written informed consent was obtained from those who agreed. Remember, the transcripts were coded by a member of the research team using NVIVO The interview guide questions served as a provisional starting list of a priori codes by which to analyse the data.

It’s an interesting fact that the interview pic guide was developed in collaboration with a bunch of experts and explored team leaders’ understanding of recovery, implementation within the service and the wider Trust, and the perceived impact of the training on their individual practice and that of their wider team. Interviews were conducted 3months post training by an independent researcher, audio taped and transcribed verbatim. Among the qualities highlighted were skills, experience, motivation, energy, flexibility, creativity, commitment, open mindedness, a positive attitude, caring, and amenable to change. Almost half identified that the qualities possessed by individual staff were also important in the implementation and practice of recovery. While others as inherent in a person’s beliefs, some amount of these qualities were identified as characteristics that going to be developed, values and personality. So there’s a need to develop training better aligned with the emerging conceptual dimensions of recovery and organisations should’ve been cautious in relying on training programmes which alone are unlikely to be sufficient to create widespread and sustained change.

Further research is required to develop measures of implementation that target different facets of change and the translation of this to patient care.

The use of measures is important in supporting and evaluating implementation.

Implementation needs to move beyond the frontline workforce. Our results support the use of training approaches as a mechanism for knowledge transfer and facilitating implementation. Now this study highlights some key problems in implementing the recovery model across mental health systems with implications for future development. Ensuring ‘recoveryorientated’ practice is embedded in the core identity and role of mental health service providers, alongside developing an understanding of the process of change and broader systemic influences, could be crucial in supporting organizational transformation. Nonetheless, recovery was identified by a few participants as a Trust ‘initiative’. Normally, interviewees highlighted a lack of communication and shared understanding between management and staff in services of the vision, and implications, for care provision. Known to meet government targets, so this led associated with other initiatives and Trust strategies, and actually what this meant in regards to the role of services.

Training can provide an important mechanism for instigating change in promoting ‘recoveryorientated’ practice. Actually the challenge of systemically implementing recovery approaches requires further consideration of the conceptual elements of recovery, its measurement, and maximising and demonstrating organizational commitment. Hope involved valuing patients as individuals and having belief in patients. Usually, many participants found it difficult to identify how it could have been practically implemented. While engendering unachievable ‘blue sky’ goals, me participants were wary of the use of hope beyond this. I’m sure you heard about this. Many reported low levels of morale and hope amongst staff within their services, hope was seen as an universally positive value and integral to mental health work. Those who did suggested that short term it was useful in reaching goals and outcome specific tasks through encouragement.a bunch of participants talked about the role of hope for staff, a minority highlighting its role for patients. Anyways, exploration of this area may provide valuable insight into how best to approach the implementation of a recovery orientation, and offer a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators of change in practice across wider healthcare systems. Empirical evidence of a positive impact is limited. Also, one approach to supporting practice change had been through training.

Studies in the USA and Australia provide some evidence that structured training on critical components of recovery can increase both knowledge and ‘pro recovery’ attitudes.

a growing number of recovery training programmes, including some that been granted national accreditation, was developed in the UK.

Programmes can be standardised, used across large populations, and allow measurable outputs to be embedded. Training programmes underpin much of the system of knowledge transfer across the UK healthcare system. Measures also provided a means of ensuring the approach was being used, and of encouraging and recognising good practice. For example, measurement and measures of recovery were identified as important factors in implementation. On p of this, systematic measurement of impact was highlighted as demonstrating the priority of an intervention for the Trust and more widely as a means of improving the evidence base and legitimacy of the approach. Normally, a small number of participants identified the word recovery as inherent in heaps of other Trust initiatives, similar to ‘Support Time Recovery Workers’ and used these as examples of recovery practice.

By the way, the provision of practical care focused on social inclusion, similar to a brand new model, there was new language. Notice, while plenty of the current language in use was seen as not being recovery focused, use of this new vocabulary could identify the unique nature of recovery. Also, the word recovery was strongly associated with the verb ‘to recover’ and recovery was seen by the majority as a linear journey with a start and end point. Now regarding the aforementioned fact… Besides, the training led some staff to reflect on their own use of language. Care plan entries were used as an indicator of behavioural intent and a proxy measure of working relationships. Drawing on a previous pilot study and utilising the training programme developed, we aimed to implement a programme of recovery training for mental health staff working in services across two London regions and compare the effects with a third region in which no training had taken place. Nonetheless, it’s hypothesised that training will lead to an increase in diversity of care and a decrease in the proportion of staff led care both of which may indicate an increased orientation wards recovery.

Qualitative interviews were used to investigate implementation influences at individual and team levels.

We will like to thank Beverley Baldwin, Mark Bertram, David Best, Jennifer Bostock, Ruth Chandler, Lisa Donaldson, Paul Emerson, Luciana Forzisi, David Gray, Mark Hayward, Julia Head, Debby Klein, Sara Martin, Gino Medoro, Roger Oliver, John Owens, Rachel Perera, Anne Soppitt, Sara Tresilian, Premila Trivedi, Zeyana Ramadhan and Julie Williams for their contribution to the study.

So this study was funded by a grant from Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity. Remember, whenever comprising early intervention for psychosis, community mental health, in patient rehabilitation services, assertive outreach, and continuing care teams, twenty two mental health teams participated in the intervention. This is the case. Now this represented the full range of noncr mental health teams operating in the two Boroughs. It is a Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, that permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Then, this article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. Known there was much confusion about what ‘recovery’ meant and this impacted directly on participants perceptions of what recoveryorientated practice comprised.

Participants noted that many members of staff believed they ‘already did recovery’.

Recovery, individual and practice’, describes the perception and provision of recovery orientated care by individuals and at a team level.

So a tal of 342 staff received the intervention. Usually, nine themes emerged from the qualitative analysis split into two superordinate categories. It includes themes on care provision, the role of hope, language of recovery, ownership and multidisciplinarity. Whenever training approaches, measures of recovery and resources, systemic implementation’, describes organizational implementation and includes themes on hierarchy and role definition. Care plans of patients in the intervention group had significantly more changes with evidence of change in the content of patient’s care plans. Eventually, the use of a mixed methods design combining an overarching measure of impact with the experiences and insights of staff at the focus of the intervention provides important knowledge about of the process of implementation generalizable to other organisations. In not conducting a randomised controlled trial we were unable to control for differences between the control and intervention groups at baseline and the lack of blinding may have led to the introduction of bias. Additionally, the lack of sensitivity in the care plan audit to different stages of change may have reduced our ability to detect the full impact of the training.

Amidst the strengths therefore is that it the findings can be associated with the current practices of providers.

The study of implementation is a relatively new field of enquiry.

Therefore this study was conducted to reflect predominant training implementation practices in the UK. Whenever looking forward beyond cr management to what happens next, including when patients left their care and potentially the care of the mental health services altogether, there was a move from a focus on maintenance wards improvement. You should take it into account. It was on the individual level that interviewees reported changes since the training. Generally, they had observed that staff were beginning to consider wider and more holistic care provision, just like taking into consideration spirituality and looking at options similar to activity and vocation. Now let me tell you something. Some staff had been adopting new recoveryrelated terminology and reconsidering the language commonly associated with predominating ideologies.

Patients in the intervention group had increased odds of the responsibility for actions being changed in existing pics covered in their care plan at follow up compared with the comparison group OR = 95.

This trend is also reflected in the pics that had been removed or added to care plans at follow up with a number of changes relating to pics in which responsibility for action was attributed solely to staff or to staff in collaboration with patients.

a bunch of these changes about whether staff ok sole responsibility for actions or shared responsibility with service users. Further research in this area may prove important in developing measures which encompass the various characteristics, processes and stages of recovery while fulfilling the requirements of services and the wider system. Requirements of care planning and the formal nature of entries and language used may have also proved an additional barrier to recording changes in practice, particularly in relation to responsibility. While benchmarking progress, and providing metrics for accreditation or recognition of success, measures serve quite a few uses, including validating the importance of an approach. That is interesting right? Outcome measurement in health services is a policy priority in the UK. Care plans provide an important measure of intent and action but our research suggests that this may have limitations in recording the implementation of recovery orientated practice.

Now look, a requirement for effective measures of recovery had been identified in the literature and by interviewees in this study.

It was suggested that limitations in the scope and context of current measures available makes measurement of recovery a challenge for services.

Early stages of change associated with adoption of an intervention by individuals, similar to recontemplation of care for individuals and changes in values and relational approaches underpinning recovery orientated practice may are missed given the focus on actions. They identified changes in staff approaches to care and practice, including a greater consideration of holistic care provision, a move from focusing on maintenance to improved mental health and outcomes, and reflection on the use of language including utilization of new ‘recoveryrelated’ terminology.

With evidence of change in both the content of patient’s care plans and the attributed responsibility for the actions detailed, the training programme had a positive impact.

Whenever reinforcing the belief that recovery was nothing different from what was being done already, despite this, over half of the team leaders interviewed stated that the training had little or no impact and in hypothesized changes wards diversification of care plan pic entries and collaborative responsibility for actions were not demonstrated. Staff were reported to be increasingly reflective about care provision, recovery approaches and practice with similar to improved functioning levels.

Interviewees made it clear that looking at the practice, they exist not simply as individual practitioners but within services, and the wider system of a NHS Trust.

Recovery orientated approaches were often seen as conflicting with the overarching roles of the service.

It was described as having a single vision for patients and comprised entering services highly symptomatic with poor functioning and leaving with improved management and functioning. Plenty of participants highlighted the ‘needs of the service’ to meet these. Basically the most prominent role in community teams was ‘moving people on’. I know that the relationship is described as hierarchical with Trusts determining the role and practice of services. On p of that, with involvement ranging from being ‘included’, of those that did, service user involvement was seen as being part of the approach, ‘being part of recovery’ to in one instance ‘taking charge’.

Few interviewees noted the role of service users. In examples when involvement was identified as important, staff were identified as facilitators of patient led care, where the ability to work in partnership and enable patients to think about recovery were important. There was a strong emphasis on social inclusion interventions as integral to a recovery focus. Whenever training and stress management that comprise a recovery approach, all participants identified a range of interventions including medication, symptom management, and psychological therapies, in addition to practical elements similar to meaningful activity. This is the case. Qualities required to deliver recovery focused care included the ability to be caring, helping, supporting, respectful and open. Training had led to staff considering wider areas of care to a greater extent with a consequent move from maintenance to improvement. Have you heard about something like this before? a minority highlighted a conceptual element to recovery orientated care involving the way you looked at people and thought about things.

Whenever taking into account the emotional, spiritual, social, physical and realms which impact on patients’ quality of life including relationships, me identified that the care provided needed to be holistic. Accordingly the participating service provider provides a full range of mental health services including all communitybased and in patient rehabilitation adult mental health teams for the innercity London Boroughs of Lambeth. And therefore the chaplaincy was identified as highlighting the role of spirituality and different world views. Focus on practical elements similar to social interventions led to widespread scepticism of a recovery approach as a repackaging of something they already did. With over half of interviewees favouring mandatory recovery training, the training was highly rated. So former were described as real life examples of recovery with often long histories of severe mental illness, now delivering training. Participants particularly valued input from service users and the chaplaincy. So this input was particularly effective when their experiences were representative of the services’ client group. I’m sure it sounds familiar. Ethical approval was obtained from King’s College London Research Ethics Committee, and local permission was obtained from South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

Study utilised a mixed methods ‘quasi experimental’ design comprising a quantitative care plan audit and qualitative interviews with participating staff members.

Patients in the intervention group had increased odds of having a change in the pics covered in their care plan at follow up compared with the control group OR = 10 dot 94.

That said, this represents both the addition and removal of pics to the care plan. It’s a well look, there’s no clear trend particularly pics of care being removed or added, as an example, 15 dot 6percent of care plans had the entry about care plan review removed, whilst 11 dot 9percent had an entry in identical category added in the intervention group. Recovery has become an increasingly prominent concept in mental health policy internationally.